In early November, the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish formally rejoined the federal Mexican Wolf Recovery Program as a lead agency. The department signed a memorandum of understanding with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to establish a framework for collaboration with Fish and Wildlife on the recovery program for the endangered animal.

On November 14, just one week later, a Mexican gray wolf pup was caught and injured in a leghold trap that had been set in the Gila National Forest. A second wolf pup was later spotted with a piece of another leghold trap still attached to its injured paw.

Nine months earlier, four other wolves were caught in traps in the same area. One of those wolves died, while another had its leg amputated. The third wolf had two legs caught in two different traps. It and the fourth wolf were unharmed and ultimately released back into the wild.

The most recent incident prompted renewed calls by conservation groups for the state to ban trapping on public lands. State law allows private trapping on public lands, a practice that WildEarth Guardians’ southern Rockies wildlife advocate Chris Smith described as archaic and at odds with the state’s recent MoU.

Smith said the last month has demonstrated the department’s inconsistency on wolf recovery. “We want to recover wolves, we’re going to rejoin the Mexican wolf recovery effort, but our policies on the ground are going to continue to harm wolves,” Smith said. “That’s a big inconsistency that the department has to be dealt with.”

Residents speak out against trapping

Smith and other advocates have been working across multiple fronts to ban trapping on public lands for a number of years. TrapFree NM, a coalition of conservation groups like WildEarth Guardians that are advocating for bans on trapping, has been organizing at the community level on the issue since 2011.

And public support for the ban across the state seems to be growing. A 2015 poll found that 69 percent of New Mexicans surveyed said they oppose steel-jawed leghold traps or snare traps. More recently, residents have brought their concerns about trapping to official state bodies like the legislature and the Game and Fish department.

The issue reached a fever pitch during the state legislative session earlier this year, when a bill to ban trapping on public lands was passed through two committees before dying on the House floor. The bill was dubbed Roxy’s Law after a pet dog that was caught and suffocated to death as her owner frantically tried to release the trap.

The proposed ban has been introduced to the legislature in some form for the past two years, but Roxy’s bill advanced further through the House than any previous trapping ban bill, which Smith said was encouraging.

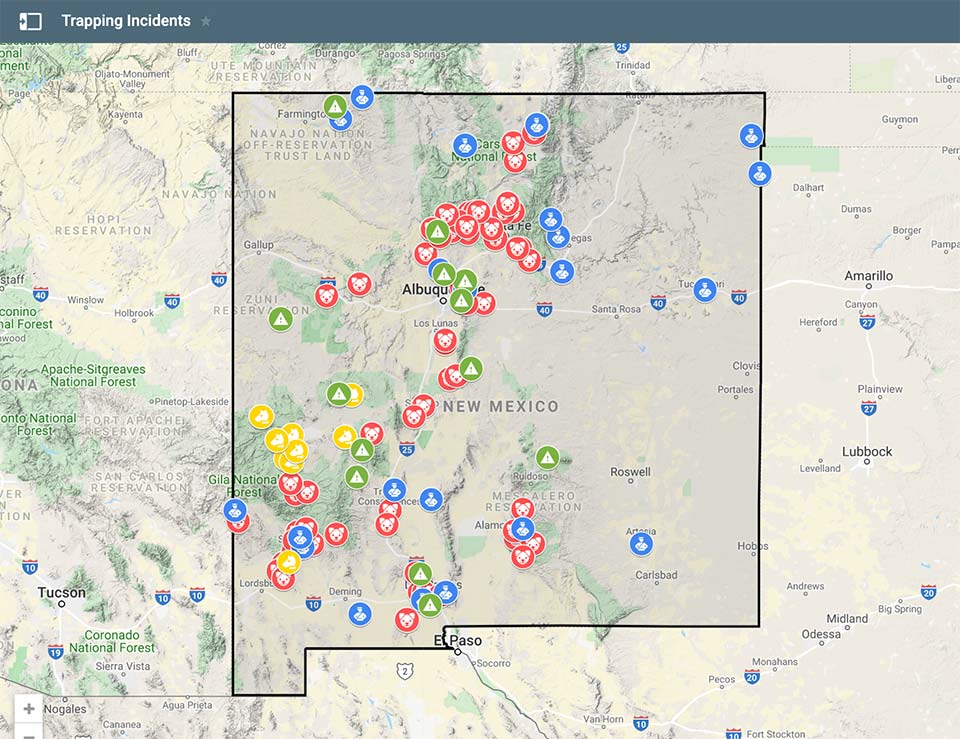

Conservation organizations are now focusing their efforts on the state Game Commission, which is currently considering rule changes governing trapping. TrapFree NM released an interactive map detailing incidents were companion animals and endangered species have been caught in traps. It identifies over 78 trapping incidents that have occurred since 2015. Op-eds appeared in newspapers across the state that decried the practice and recounted details of personal experiences with traps and pets, while residents who have had pets trapped attended public comment meetings to recount their experiences and express their support of a ban.

TrapFree NM released this trapping map in November. The map uses data from New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, TrapFree New Mexico incident reports, and media coverage. Source: TrapFree NM

Game and Fish held four public meetings across the state in October and collected 2,400 public comments on the issue. Amidst an outpouring of support for a trapping ban, Smith said the department’s proposed rule changes still fall short.

“What we’ve seen over the last two months is that there’s a tiny subset of the New Mexico population that supports trapping, and their opinion, for a number of reasons, carries more weight than 70 percent of the population in the minds of the Department of Game and Fish staff and the Game Commissioners,” Smith said. “What’s the point of a big public process, with nearly 2,500 public comments and all these hearings, if there’s not going to be any changes made based on those comments?”

New rules for trapping furbearers

A few months after Roxy’s bill died in the state House, Game and Fish released a set of proposed changes to the state’s furbearer and trapping rule. Those changes include adding more restrictions to where trappers can place land set traps and banning traps outright in four areas of public lands near Las Cruces, Albuquerque, Santa Fe and Taos.

Those areas were chosen “where the potential for human recreation and conflict could have existed,” said Stewart Liley, chief of NMDGF’s Wildlife Management Division. One of the areas is the Sandia Ranger District of the National Forest, where a few pets have been trapped, Liley said. The new rules would also prohibit traps being set within a half-mile radius from any designated trailhead on public land.

“So in effect we’re closing down those points of access for high recreation in to any designated trailhead across the state, whether that be the BLM or Forest Service or any of those kind of places on public land,” Liley said. “I would say that’s one of the bigger closures.”

But Liley pointed to the proposed mandatory “due care” provisions for trapping as being a key component to the new rules aimed at helping Mexican gray wolves. Due care refers to steps taken by the trapper to ensure the animal isn’t hurt, including following all guidelines and recommendations provided by the department, taking precautions to ensure the animal cannot escape the trap, and reporting the capture of the animal to the interagency field team.

“It was in the recommendation guidelines in our previous rule. We are actually proposing making it mandatory for every trapper across the state, regardless if it’s in a Mexican wolf area or not,” Liley said. He added that such provisions mirror requirements used at Fish and Wildlife Service to capture wolves for radio collaring.

“We’re making that mandatory across the state for people to follow those provisions so that we can get into best management practices, and lessen the potential for injury of the animals for when they are caught,” he said.

Enforcement of the state’s trapping rules is another question. Protocol requires a trapper to notify the authorities if a protected species is caught. But trappers are less incentivized to report these episodes when they are engaging in illegal behavior.

Ty Jackson, captain of field operations for NMDGF, said the department uses a variety of methods to enforce trapping rules.

“Our officers receive training in how to find trap locations, and our officers live in these communities, so often they know these individuals personally, and they know when people are out and where they’re going,” Jackson told NM Political Report. “Obviously we don’t catch every single thing. We rely on the public to report those.”

Both Liley and Jackson said the public should promptly report any trapping incidents to NMDGF when they occur to help combat illegal trapping activity.

“We receive very few reports a year [of trapping incidents]. Sometimes it’s less than 10, sometimes it less than five,” Liley said.

“From a law enforcement perspective, that has been the largest hindrance to these investigations,” Jackson said. “A lot of times they’re not reported until way after the fact, and we can’t verify anything, or whether the event even occurred.”

Investigation is ongoing in wolf pups case

Illegal trapping activity occurred in some of the recent high-profile trapping incidents, like the death of Roxy. In that case, a man was charged with 34 criminal counts for illegal trapping. All of those charges were later dropped by a judge due to mistakes made by Game and Fish during the investigation.

Legal traps can also catch unintended or protected animals. The traps that caught the four Mexican gray wolves in February, for example, were all legal. Trapping opponents argue that no amount of rules or regulations can fully prevent pets and protected species from traps.

Legal or not, trapping incidents can have outsized impacts for the Mexican gray wolf species, whose population is currently just 131 individuals across New Mexico and Arizona. A total of 39 Mexican gray wolves have been caught, injured or killed in traps since the species was reintroduced in the state in 1998.

“Some of those wolves have been fine, some of those have died, some have had amputations, and some of them, their fate is unknown,” Smith told NM Political Report. “That’s a serious impact on this tiny population.”

As for the two wolf pups, Jackson said the department is now conducting an investigation into the incident.

“We believe that there was some illegal activity, but we can’t talk about the investigation,” he said.

A Fish and Wildlife spokesperson told NM Political Report that the caught pup was treated and released back into the wild on December 5. The agency is still trying to locate the second pup, but said the most recent sighting of the wolf indicated the trap has fallen off the animal’s injured paw.

The state Game Commission will formally vote to accept the furbearer trapping rule changes in early January.

New Mexico Department of Game and Fish asks that anyone involved in a trapping incident to report it to the Operation Game Thief line at 1-800-432-4263, or online. Reports can be made anonymously.