Robert Harrison, Ph.D, University of New Mexico[1]

December, 2020

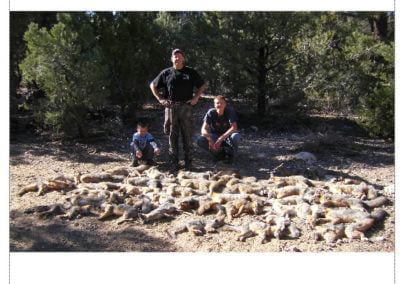

Summary: Wildlife enthusiasts are well aware of the potential of leghold traps to severely injure wild animals. Less appreciated is how many wild animals suffer such injuries in the course of an average trapping season. I used leghold trap injury rates reported in published studies combined with the numbers of animals reported caught by the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish to estimate the number of wild animals injured annually in New Mexico. Based upon an average reported catch (harvest) and an average estimated catch (based upon harvest reporting rates) of 10,846 and 12,893 animals, respectively, from 2010 through 2020, I estimate that 5,315 to 6,318 animals in New Mexico annually suffer serious or severe injuries such as broken bones, severed tendons, deep cuts, dislocated joints, and broken teeth.

The use of leghold traps (a.k.a. foothold or steel traps) has drawn controversy for decades1,2,3. Efforts to find more humane alternatives for animal capture began at least as early as the 1940’s4. Studies have compared injury rates of traditional leghold traps with modified leghold traps and other types of traps (Notes 5-19). Studies used in this report were published in peer-reviewed scientific journals, primarily the Journal of Wildlife Management and the Wildlife Society Bulletin, which are the two premier journals of the wildlife management profession. To simplify this brief report, I do not include scientific names for animals and use common terms for injuries rather than medical jargon.

The New Mexico Department of Game and Fish (NMDGF) allows the use of traditional leghold traps of jaw spread less than seven inches20. The only required modifications are a 3/16″ offset (gap) between the jaws when the trap is closed if the jaw spread is less than or equal to 5-1/2,” and lamination if trap jaw spread is between 6-1/2 and 7″. It is unknown how many New Mexico trappers use offset traps, other types of traps, or traps with additional modifications. For these reasons, I assume for this report that all New Mexico trappers use traditional leghold traps with a 3/16″ offset.

Many different species have been included in injury studies, with coyotes being the most common. Other species included in the studies reviewed here were red, gray, and arctic foxes, bobcats, raccoons, wolves, opossums, skunks, dogs, cats, porcupines, groundhogs, weasels, sheep, squirrels, and snowshoe hares.

Several systems to rate the severity of injuries have been used. The two most common are a simple four-level system and a point system. In the four-level system, Level One includes no or slight injuries, Level Two includes moderate swelling, chipped teeth, and small cuts, Level Three includes medium cuts with damage to underlying tissues, minor joint dislocations, broken teeth, hairline fractures, and one or less toe bone broken. Level Four includes deep cuts, swelling that prevents an animal from using the injured limb, severed tendons, major joint dislocations, frozen feet, and broken bones. Level Three is considered serious injury, and Level Four is considered severe injury.

In the point system, points are given for each injury8. For example, 5 points for minor swelling and bleeding, 20 points for tendon and ligament cuts, 50 points for major joint dislocation, 75 points for compound fractures near the wrist or ankle, 200 points for compound fractures away from the wrist or ankle, and 400 points for amputated limbs. Points are added for each injury to yield a total score for each animal. Total scores of 50-100 are considered to be serious, and total scores over 100 are considered to be severe.

Most studies employed veterinary pathologists to perform thorough necropsies, including the use of x-rays. A few, mainly older, studies used external evaluations by non-veterinarians. The latter studies most likely underestimated the extent of injuries.

The average percentage of caught animals receiving serious and severe injuries reported by those studies using the four-level system or an equivalent was 49% (range 24-86%, 11 studies). The average injury score from studies using the point system was 94 (range 44-150, 7 studies). A score of 94 is very serious and nearly severe.

Figures presented in the previous paragraph were from studies of traps with no offset. The number of studies including offset traps is very limited. One other study that included traps with an offset of 1/5″ reported an average injury score of 8016. A second study reported a serious or severe injury percentage of 41% for unmodified traps and a serious or severe injury rate of 38% for traps offset by 1/12″18. To my knowledge, no significant advantage from offsetting has been reported. I found no studies of lamination.

For comparison, guidelines issued by the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (AFWA) include criteria for approval for the use of specific traps for specific species21. AFWA conducted injury studies on various species using a variety of traps. One set of criteria required that average total injury scores must be 55 or less. The other set allowed 30% of animals to suffer serious or severe injuries. The former criterium does not indicate what percentage of animals suffer scores of more than 55. These criteria are stricter than the average injury rates found for traditional leghold traps in the studies reviewed here. However, there is no requirement by NMDGF that trappers adhere to the guidelines or use recommended traps.

AFWA guidelines approved specific traps for specific target species. There was no consideration of injuries to captured non-target animals. Although there are modifications available to traps that prevent animals below a certain weight from being captured, such modifications are not required by NMDGF, and trappers are unlikely to use them. Smaller animals caught may suffer far more severe injuries than larger animals in the same trap. One study which focused on coyotes reported that snowshoe hares had an average total injury score of 209, and smaller animals such as squirrels were usually found dead10.

There are two methods available to estimate the numbers of furbearering animals caught in New Mexico each year. Trappers are required to report their catches, leading to a reported total catch (harvest). However, not all trappers report. Accounting for the percentage of trappers not reporting leads to an estimated total catch (= reported catch/reporting fraction). The actual numbers of animals caught lies in between the two estimates.

Based upon NMDGF published Furbearer Harvest Reports22 from the 2010/2011 through the 2019/2020 seasons, the average number of furbearers reported caught was 10,846 per year. The estimated average number of furbearers caught based upon reporting rates was 12,893 per year23. These figures include red, gray, kit, and swift foxes, badgers, beavers, coyotes, bobcats, ermines, weasels, muskrats, nutrias, raccoons, and ringtails (See Note 24 for treatment of coyotes and skunks). At an average serious or severe injury rate of 49%, between 5,315 and 6,318 wild animals received serious or severe injuries as a result of being caught in a leghold trap. At an average injury score of 94, most animals received serious or severe injuries. These high rates of injury are what prompted the many studies of alternatives to traditional leghold traps.

It is impossible for most people to fully understand the experience of a trapped animal, injured and vulnerable to attack by larger predators. We do know that trapped animals experience significant levels of stress, as shown by increased levels of hormones, serum chemicals, and immune system activity25, 26. Given that all mammals, including ourselves, have similar nervous and endocrine systems and brain structure, it is fair to say that the reactions that trapped animals have to being in pain and in fear for their lives would be quite similar to the agony and horror we ourselves would feel in a similar situation. Certainly, soldiers in combat, severely wounded and exposed to enemy fire, would understand. In New Mexico, the extent of these grisly misfortunes can only be described as horrendous.

Notes:

- Muth, R. M., R. R. Zwick, M. E. Mather, J. F. Organ, J. J. Daigle, and S. A. Jonker. 2006. Unnecessary source of pain and suffering or necessary management tool: Attitudes of conservation professionals toward outlawing leghold traps. Wildlife Society Bulletin 34(3):706-715.

- Andelt, W. F., R. L. Phillips, R. H. Schmidt, and R. Bruce Gill. 1999. Trapping furbearers: an overview of the biological and social issues surrounding a public policy controversy. Wildlife Society Bulletin 27(1):53-64.

- Proulx, G., M. Cattet, T. L. Serfass, and S. E. Baker. 2020. Updating the AIHTS trapping standards to improve animal welfare and capture efficiency and selectivity. Animals 10:1262; doi:10.3390/ani10081262.

- Robinson, W. B. 1943. The “Humane Coyote-Getter” vs. the Steel Trap in Control of Predatory Animals. Journal of Wildlife Management 7(2):179-189.

- Linhart, S. B., G. J. Dasch and F. J. Turkowski. 1981. The steel leg-hold trap: Techniques for reducing foot injury and increasing selectivity. Pp. 1560-1578 in J. A. Chapman and D. Pursley, eds. Worldwide Furbearer Conference Proceedings. R. R. Connelley & Sons, Co., Falls Church, VA.

- Novak, M. 1981. The foot-snare and the leg-hold traps: A comparison. Pp. 1671-1685 in J. A. Chapman and D. Pursley, eds. Worldwide Furbearer Conference Proceedings. R. R. Connelley & Sons, Co., Falls Church, VA.

- Englund, J. 1982. A comparison of injuries to leg-hold trapped and foot-snared red foxes. Journal of Wildlife Management 46(4):1113-1117.

- Olsen, G. H., S. B. Linhart, R. A. Holmes, G. J. Dasch, and C. B. Male. 1986. Injuries to coyotes caught in padded and unpadded steel foothold traps. Wildlife Society Bulletin 14(3):219-223.

- Olsen, G. H., R. G. Linscombe, V. L. Wright, and R. A. Holmes. 1988. Reducing injuries to terrestrial furbearers by using padded foothold traps. Wildlife Society Bulletin 16(3):303-307.

- Onderka, D. K., D. L. Skinner and A. W. Todd. 1990. Injuries to coyotes and other species caused by four models of footholding devices. Wildlife Society Bulletin 18(2):175-182.

- Phillips, R. L., F. S. Blom, G. J. Dasch, and J. W. Guthrie. 1992. Field evaluation of three types of coyote traps. Pages 393-395 in J. E. Borrecco and R. E. Marsh, eds. Proceedings of the Fifteenth Vertebrate Pest Conference. Newport Beach, California, USA.

- Warburton, B. 1992. Victor foot-hold traps for catching Australian brushtail possums in New Zealand: capture efficiency and injuries. Wildlife Society Bulletin 20(1):67-73.

- Proulx, G., I. M. Pawlina, D. K. Onderka, M. J. Badry and K. Seidel. 1994. Field evaluation of the number 1 1/2 steel-jawed leghold and the Sauvageau 2001-8 traps to humanely capture arctic fox. Wildlife Society Bulletin 22(2):179-183.

- Phillips, R. L. 1996. Evaluation of three types of snares for capturing coyotes. Wildlife Society Bulletin 24(1):107-110.

- Hubert, G. F. Jr., L. L. Hungerford, G. Proulx, R. D. Bluett, and L. Bowman. 1996. Evaluation of two restraining traps to capture raccoons. Wildlife Society Bulletin 24(4):699-708.

- Hubert, G. F., Jr., L. L. Hungerford, and R. D. Bluett. 1997. Injuries to coyotes captured in modified foothold traps. Wildlife Society Bulletin 25(4):858-863.

- Earle, R. D., D. M. Lunning, V. R. Tuovila, and J. A. Shivik. 2003. Evaluating injury mitigation and performance of #3 Victor Soft Catch® traps to restrain bobcats. Wildlife Society Bulletin 31(3):617:629.

- Frame, P. F., and T. J. Meier. 2007. Field-assessed injury to wolves captured in rubber-padded traps. Journal of Wildlife Management 71(6):2074-2076.

- Turnbull, T. T., J. W. Cain, III, and G. W. Roemer. 2011. Evaluating trapping techniques to reduce potential for injury to Mexican wolves. Unpublished report to NMDGF. Open file report 2011-1190. USGS.

- NMDGF 2020-2021 New Mexico Furbearers Rules and Information. General Rules. Page 12. Restrictions applying to all traps that could reasonably be expected to catch a furbearer. Size Restrictions. www.wildlife.state.nm.us/hunting/information-by-animal/furbearers. Accessed 22 December, 2020.

- Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. 2006. Best Management Practices for trapping in the United States. Page 5. www.fishwildlife.org/application/files/3515/1862/6191/Introduction_BMPs.pdf. Accessed 22 December, 2020.

- NMDGF Harvest Reports. www.wildlife.state.nm.us/hunting/information-by-animal/furbearers. Accessed 22 December, 2020.

- The average reporting rate from 2010/2011 through 2019/2020 was 82.3%.

- Coyotes and skunks caught by trappers have not been recorded by NMDGF since 2014. To estimate their numbers, I applied the average catch from 2010/2011 through 2013/2014 to 2014/2015 through 2019/2020. Average reported catches applied were 5006 for coyotes and 443 for skunks. Average estimated catches applied were 6177 for coyotes and 553 for skunks.

- Kreeger, T. J., P. J. White, U. S. Seal, and J. R. Tester. 1990. Pathological responses of red foxes to foothold traps. Journal of Wildlife Management 54(1):147-160.

- White, P. J., T. J. Kreeger, U. S. Seal, and J. R. Tester. 1991. Pathological responses of red foxes to capture in box traps. Journal of Wildlife Management 55(1):75-80.

[1] Dr. Robert Harrison is an Adjunct Assistant Professor at the Biology Department of the University of New Mexico and a native of New Mexico. His Ph.D research was a study of the effects of residential development on gray foxes in New Mexico. He has published over 40 peer-reviewed articles on bobcats, swift, kit, red, and gray foxes, badgers, ringtails, and rabbits, and has followed furbearer trapping issues in New Mexico for 28 years.